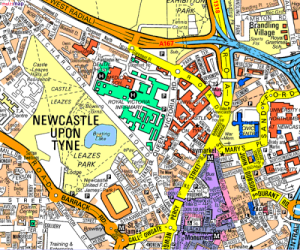

I am living in a city that one could say is profoundly defined by its absences. A huge section of its heart is missing, and in its place is an intestinal creep of a shopping mall built in the early 1970s over the site of terraces and streets built in 1824. It is currently hemorrhaging from its south-westerly point over the site of an old market and now-demolished Georgian terraces. Cheap looking and indecently high, this new development will house yet another gigantic department store, dwarfing the tiny businesses on the opposite side of the street and eventually running them into the ground, creating more streets that are beginning to house spectral impressions of commerce; more absences. We are becoming passive observers watching the city self-regulate itself, and a city where traditional notions of psychogeography become more difficult to practice. In other words this architectural monolithicism of Newcastle’s redevelopment begins to skewer the ability to view the present through the prism of the past. It denies us free movement across the city, and equally as importantly, by the leveling of entire quarters of buildings and streets and passageways and alleys and nooks and crannies, it denies the vertical descent through the past – and the tendancy for gothic imagination – that is so critical to some aspects of psychogeography (Coverley) – this is nothing new in Newcastle, the city’s topography is already a rather odd and dislocated one, with a north/south motorway ripping straight through cutting off the mainly residential east from the city centre – so it becomes increasingly difficult to envision how to undermine/suspend the everyday when the urban centres we live in aren’t necessarily in a state of decay anymore, aren’t abandoned and imbued – as the situationists implied – with hidden wonders and visions to be drawn out, but are developments of enormous featureless, windowless and subjugating blocks that force us unsurprisingly into a total non-negotiation with the urban. Places like Eldon Square in Newcastle, and more recently, Liverpool One, and Belfast’s Victoria Square demonstrate an aspiration towards a technocratic revisionism, whereby whole quarters of city centres are bulldozed to create new spaces of what Kenneth Frampton calls ‘absolute placelessness’, where sites’ prehistories are expunged forever, and the potential for a transformation/evolution across time erased completely. The notion of urban regeneration through the cultivation of a site has been mostly disregarded, and new buildings tend to no longer embody the the layers of local histories that give us our individual senses of place. In fact, they tend to look so absolutely identical that Belfast, Liverpool and Newcastle become the same city centre. (As Kenneth Frampton puts it, ‘Through this layering into the site the idiosyncrasies of places find their expression without falling into sentimentality’). The ability to read a site is significantly weakened and it becomes very difficult to reconstitute a place by way of local histories, poetry, and imagination when standing in front of an impotent concrete slab. Opportunities for finding new ways of apprehending and interrogating our environment are diminishing. Architecture in this case is absolutely defining how we operate, and, contrary to utopian claims of architects and developers that new architecture can allow for new practices of living to evolve, is simply serving to accommodate consumerism. These are oppressively determinate spaces that cannot tolerate any user-defined appropriation for fear of unpredictability or destabilization, for fear of undermining established social relations. Architecture can perhaps only overcome this through the creation of fluid spaces that are open and indeterminate enough to allow for some sort of collective interpretation that is itself always open to reconfiguration. Predefined mainstream social relations can then be destabilized and put up for subversion – as they should always be.

I am living in a city that one could say is profoundly defined by its absences. A huge section of its heart is missing, and in its place is an intestinal creep of a shopping mall built in the early 1970s over the site of terraces and streets built in 1824. It is currently hemorrhaging from its south-westerly point over the site of an old market and now-demolished Georgian terraces. Cheap looking and indecently high, this new development will house yet another gigantic department store, dwarfing the tiny businesses on the opposite side of the street and eventually running them into the ground, creating more streets that are beginning to house spectral impressions of commerce; more absences. We are becoming passive observers watching the city self-regulate itself, and a city where traditional notions of psychogeography become more difficult to practice. In other words this architectural monolithicism of Newcastle’s redevelopment begins to skewer the ability to view the present through the prism of the past. It denies us free movement across the city, and equally as importantly, by the leveling of entire quarters of buildings and streets and passageways and alleys and nooks and crannies, it denies the vertical descent through the past – and the tendancy for gothic imagination – that is so critical to some aspects of psychogeography (Coverley) – this is nothing new in Newcastle, the city’s topography is already a rather odd and dislocated one, with a north/south motorway ripping straight through cutting off the mainly residential east from the city centre – so it becomes increasingly difficult to envision how to undermine/suspend the everyday when the urban centres we live in aren’t necessarily in a state of decay anymore, aren’t abandoned and imbued – as the situationists implied – with hidden wonders and visions to be drawn out, but are developments of enormous featureless, windowless and subjugating blocks that force us unsurprisingly into a total non-negotiation with the urban. Places like Eldon Square in Newcastle, and more recently, Liverpool One, and Belfast’s Victoria Square demonstrate an aspiration towards a technocratic revisionism, whereby whole quarters of city centres are bulldozed to create new spaces of what Kenneth Frampton calls ‘absolute placelessness’, where sites’ prehistories are expunged forever, and the potential for a transformation/evolution across time erased completely. The notion of urban regeneration through the cultivation of a site has been mostly disregarded, and new buildings tend to no longer embody the the layers of local histories that give us our individual senses of place. In fact, they tend to look so absolutely identical that Belfast, Liverpool and Newcastle become the same city centre. (As Kenneth Frampton puts it, ‘Through this layering into the site the idiosyncrasies of places find their expression without falling into sentimentality’). The ability to read a site is significantly weakened and it becomes very difficult to reconstitute a place by way of local histories, poetry, and imagination when standing in front of an impotent concrete slab. Opportunities for finding new ways of apprehending and interrogating our environment are diminishing. Architecture in this case is absolutely defining how we operate, and, contrary to utopian claims of architects and developers that new architecture can allow for new practices of living to evolve, is simply serving to accommodate consumerism. These are oppressively determinate spaces that cannot tolerate any user-defined appropriation for fear of unpredictability or destabilization, for fear of undermining established social relations. Architecture can perhaps only overcome this through the creation of fluid spaces that are open and indeterminate enough to allow for some sort of collective interpretation that is itself always open to reconfiguration. Predefined mainstream social relations can then be destabilized and put up for subversion – as they should always be.

As we are being shunted further from the histories and narratives of the cities we live in, physical place seems to become less and less important to how we constitute our notions of the self (this isn’t necessarily a bad thing). The ability to sense a place as a place-through-time is neutralized and undermined by the demolition of buildings (and pathways) inscribed with many many layers and impressions of use in favour of the construction of sprawling ‘placeless’ spaces which, by their design, are devoid of any capacity to embody the prehistory of the area. These constructions erase the traces and imprints of the people and populations from the constitutions of cities. They are designed to house the large retail chains familiar to every city, which dislocates one from apprehending any traces of locational identity. It is perhaps unsurprising then that most of us walk our cities with a rather cynical detachment. The indistinguishable nature of modern city centre spaces (as well as suburban areas) intensifies this alienation, and almost completely hampers old surrealist and situationist strategies of designating specific areas of cities as harbours of emotional effects to which one would consciously expose oneself as a means to transcend the everyday. However in the past one didn’t necessarily need to psychologically differentiate between areas in a city in order to create a semi-fictional playground of locational identities, as the seeping rationalization of urban assemblages that had built up over hundreds of years hadn’t quite taken hold – cities were aggregations of intense social/cultural differences and particulars.

Where current (urban) site-specific art can be situated in light of this is therefore, as Miwon Kwon suggests, as work that seeks to re-imagine difference, rather than, as early site specific art was, work that exploited difference that was apparent. However, this is also problematic. [More to come!]

Perhaps one interesting tributary from this – which has been beautifully documented by Katharine Harmon in You Are Here: Personal Geographies and Other Maps of the Imagination – is how we literally map our imagination onto places, and how we create our own personal contours of our experience. What is it that drives this compulsion to create associative imaginary maps of our landscapes? It certainly seems like the more introverted sibling of the situationist/surrealist wanderers, where information and imagination collide to form maps that are perhaps less about navigation than cultural representation, demonstrating that each person’s image of their surroundings is radically different from the next, however, as Harmon’s book illustrates, maps of the imagination were being made many many centuries before the flâneurs stalked the streets of Paris and documented their wanderings, or Debord and his cohorts began their situationist re-imaginings of the city. This is a good exhibition at the British Gallery that shows how maps were used as propaganda tools and demonstrations of power/rule/authority.

Discussion

No comments yet.